__________________________

Notes

1. Letter from Walter Reed to Emilie Lawrence Reed, December 31, 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection, 1806-1995. Box-folder 22:62. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

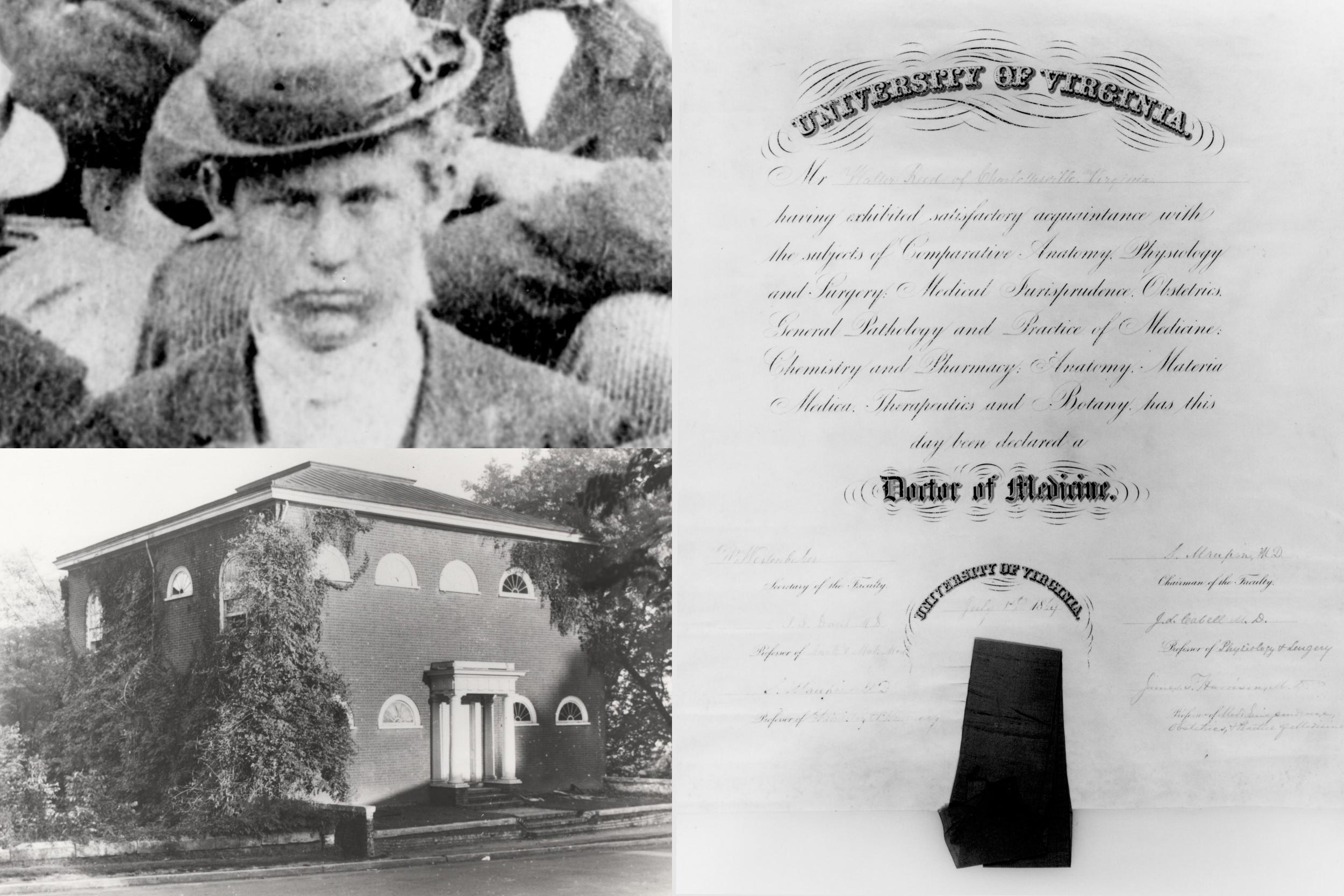

2. University of Virginia. (1869). Catalogue of the University of Virginia, 1868-1869. Baltimore: The Sun Book and Job Printing Establishment. p. 14.

3. For a more comprehensive biography of Walter Reed see: Bean, William B. (1982). Walter Reed: A Biography. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

4. Carey, Mathew. (1794). A Short Account of the Malignant Fever: Lately Prevalent In Philadelphia… To Which Are Added, Accounts of the Plague In London and Marseilles. 4th ed., improved. Philadelphia: Printed by the author. and Jones, Absalom, Richard Allen, and Matthew Clarkson. (1794). A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity In Philadelphia, In the Year 1793: and a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown Upon Them In Some Late Publications. Philadelphia: Printed for the authors, by William W. Woodward, at Franklin’s Head, no. 41, Chesnut-Street.

5. Carrigan, Jo Ann. (1961). The Saffron Scourge: a History of Yellow Fever In Louisiana, 1796-1905. 1961. Thesis–Louisiana State University of Agricultural and Mechanical College. pg. 184. Other more recent works about the 1878 epidemic include: Bloom, Khaled J. (1993). The Mississippi Valley’s Great Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. and Crosby, Molly Caldwell. (2006). The American Plague: the Untold Story of Yellow Fever, the Epidemic That Shaped Our History. New York: Berkley Books.

6. Reed, Walter. (1911). “The propagation of yellow fever — observations based on recent researches,” in United States Senate Document No. 822, Yellow Fever A Compilation of Various Publications. Washington: Government Printing Office. p. 92.

7. Letter from Walter Reed to Laura Reed Blincoe, April 4, 1902. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection, 1806-1995. Box-folder 140:20. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

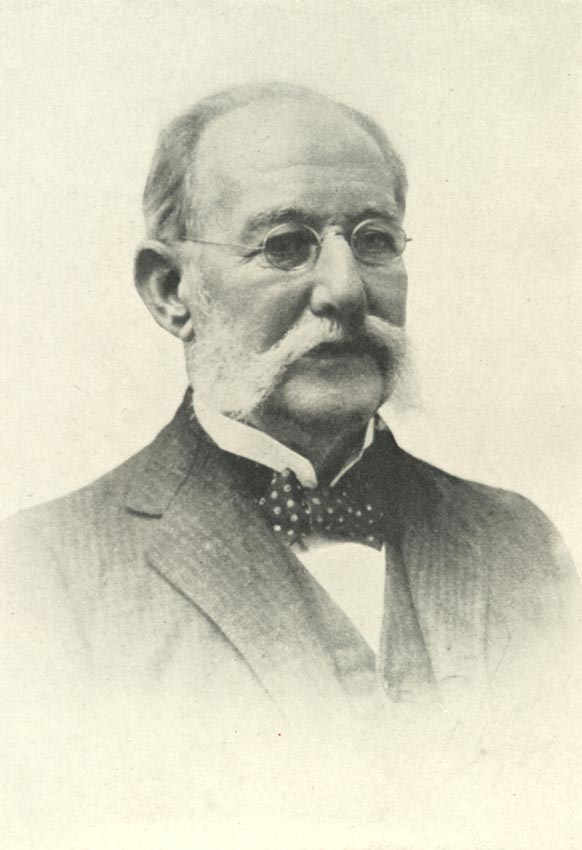

8. Finlay, Carlos J. (1881). “The Mosquito Hypothetically Considered as the Agent of Transmission of Yellow Fever.” Translated by Carlos J. Finlay. Trabajos Selectos Del Dr. Carlos J. Finlay: Selected Papers of Dr. Carlos J. Finlay. Habana, Cuba, 1912. pg 42. Reprint of an article by Carlos J. Finlay that was first published in: Anales de la Academia de Ciencias Médicas, Físicas y Naturales de la Habana, Volume 18, 1881.

9. In her study on the relationship between yellow fever and Cuban independence, Mariola Espinosa argued that the U.S. Army occupation government’s efforts to control yellow fever in Cuba were largely motivated by a concern about the spread of the disease to the United States. See Espinosa, Mariola. (2009). Epidemic Invasions: and the Limits of Cuban independence, 1878-1930. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

10. See Havard, V. (1901). “Sanitation and yellow fever in Havana, report of Major V. Havard, Surgeon U.S.A.” In Civil Report of Major General Wood, Military Governor of Cuba 1900, Vol. 4. Havana: United States Government. p. 12-13.

11. Reed, Walter. (1911). “The propagation of yellow fever — observations based on recent researches,” in United States Senate Document No. 822, Yellow Fever A Compilation of Various Publications. Washington: Government Printing Office. p. 94.

12. Reed, Walter; Carroll, James; Agramonte, Aristides; and Lazear, Jesse W. (1900). “The etiology of yellow fever — a preliminary note,” Proceedings of the Twenty-eighth Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association Indianapolis, Indiana, October, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 26, 1900.

13. Letter from Walter Reed to James Carroll, September 7, 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995. Box-folder 153:12. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. The originals of these letters remain in a private collection.

14. Ibid.

15. Fever Chart for Jesse Lazear, September 19, 1900-September 25, 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection, 1806-1995. Box-folder3:47. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library.

16. Crosby, Molly Caldwell. (2006). The American Plague: The Untold Story of Yellow Fever. The Epidemic that Shaped Our History. New York City: Berkley Books. pp. 191-197.

17. November 2, 1900. “The Mosquito Hypothesis.” The Washington Post. pg. 6.

18. Reed, Walter; Carroll, James; and Agramonte, Aristides. (1911). “The etiology of yellow fever — an additional note,” in United States Senate Document No. 822, Yellow Fever A Compilation of Various Publications. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 70-89. p. 70.

19. For a copy of the Spanish contract see: Informed consent agreement between Antonio Benigno and Walter Reed, November 26, 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995. Box-folder 70:3 [oversize]. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia. For an English translation of the contract see: English translation [from Spanish] of informed consent agreement between Antonio Benigno and Walter Reed, November 26, 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995. Box-folder 70:4 [oversize]. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

20. Letter from Walter Reed to Emilie Lawrence Reed, December 2, 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995. Box-folder 22:24. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia.

21. Moran, John J. (circa 1950). Memoirs of a Human Guinea Pig. [unpublished autobiography]. p. 1. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995. Box-folder 25:71.

22. Reed, Walter; Carroll, James; and Agramonte, Aristides. (1911). “The etiology of yellow fever — an additional note,” in United States Senate Document No. 822, Yellow Fever A Compilation of Various Publications. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 70-89. pp. 71-81.

23. ibid, p. 82.

24. ibid, pp. 83-87.

25. ibid

26. Letter from William C. Gorgas to Henry R. Carter, December 13, 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection 1806-1995. Box-folder 22:37. Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library.

27. Reed, Walter; Carroll, James; and Agramonte, Aristides. (1911). “The etiology of yellow fever — an additional note,” in United States Senate Document No. 822, Yellow Fever A Compilation of Various Publications. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 70-89. pp. 87-88.

28. Ibid, pp. 88-89.

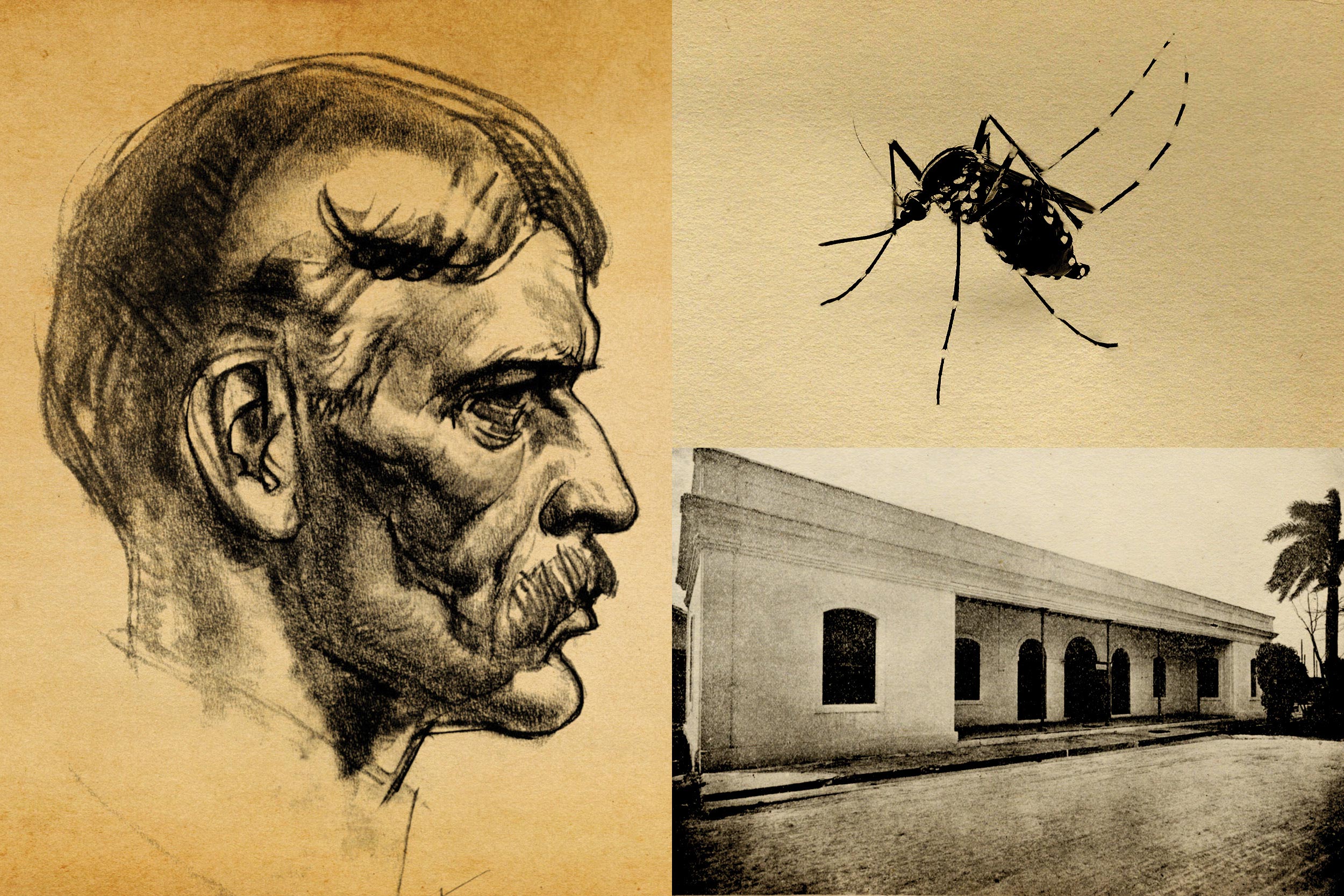

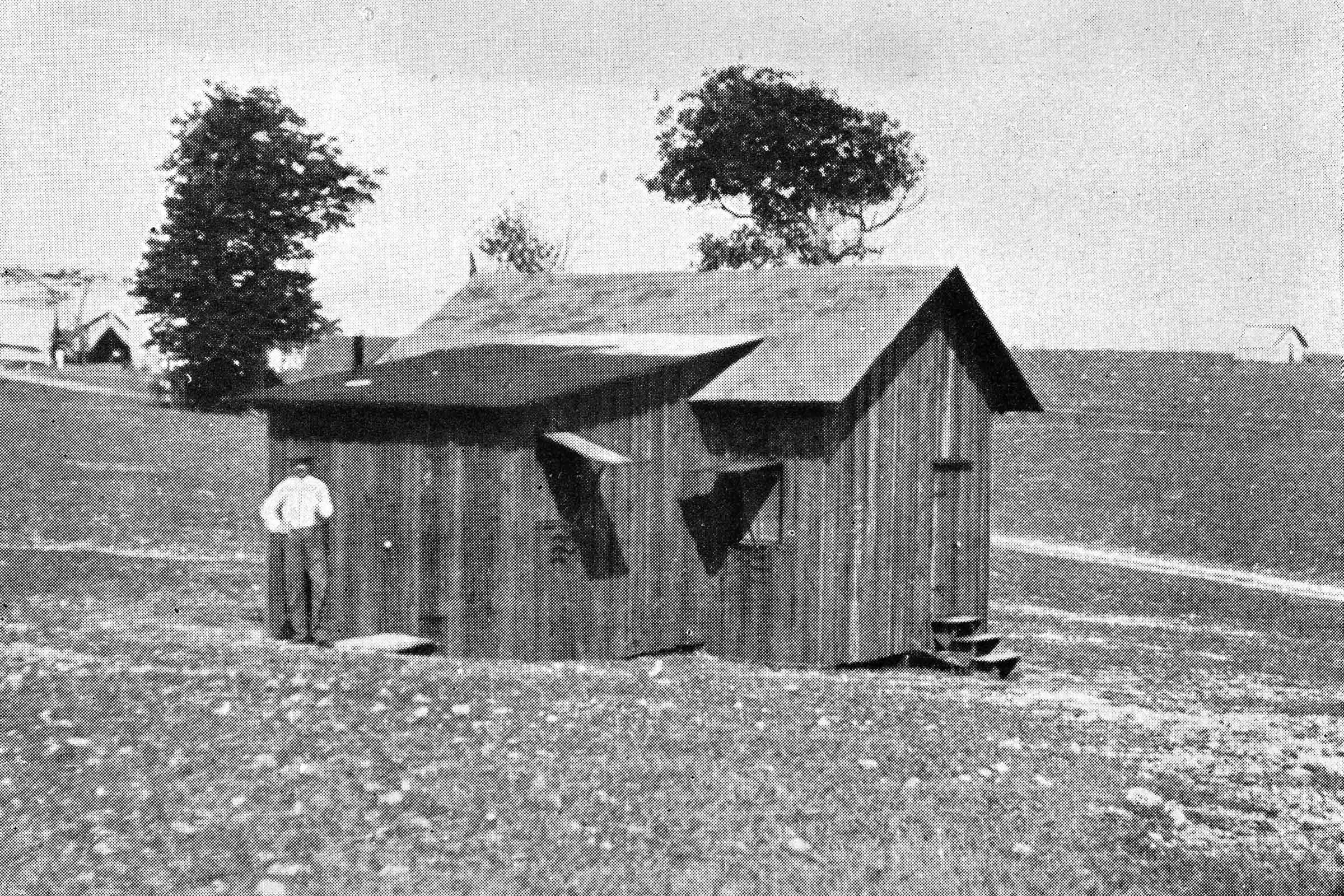

Photo at of Camp Lazear published under Creative Commons.